Creating Virtual Safe Spaces for Young People from Marginalized Communities

Sharin D'souza, 23 | ![]() Delhi, India

Delhi, India

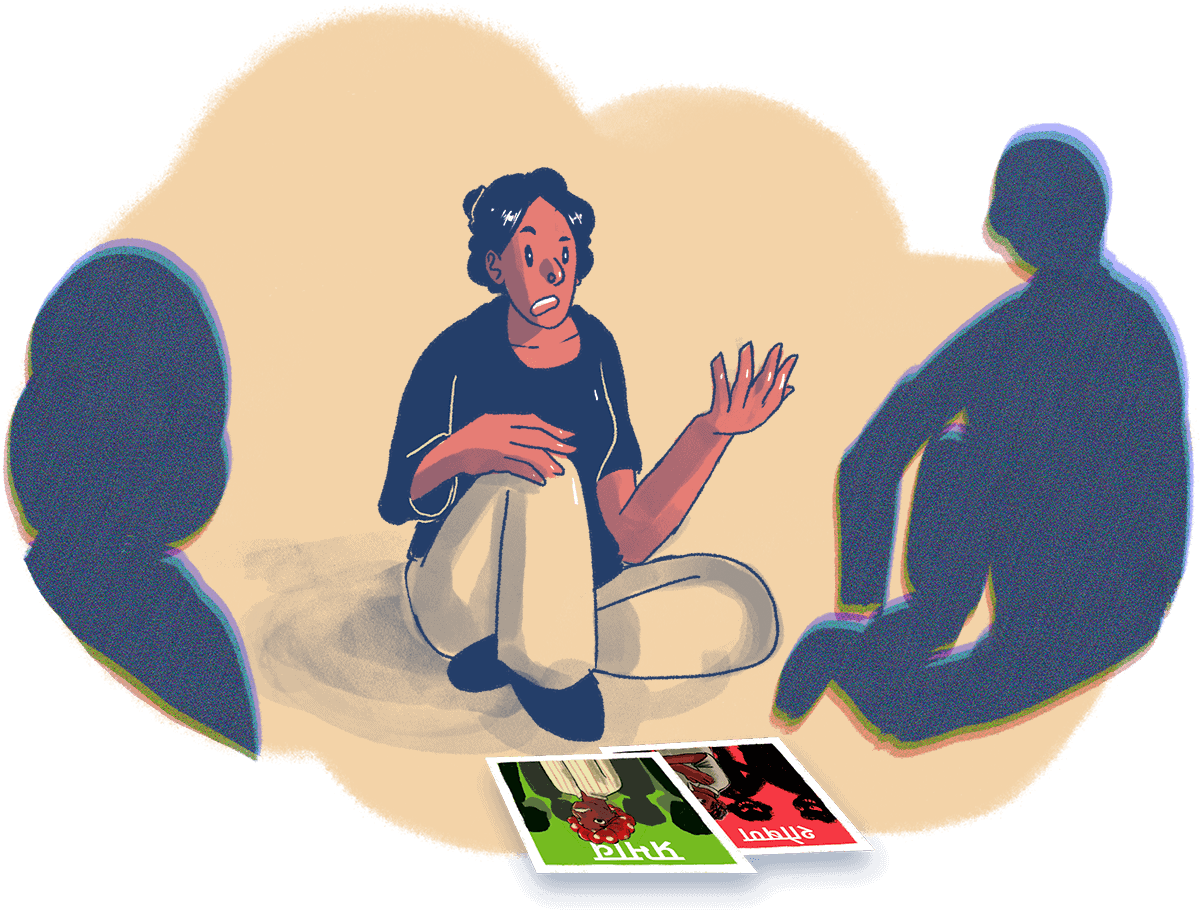

On a video call with my friends recently, I was struck by how much I censor myself while discussing subjects like relationships or sexuality at home, with my parents around. I noticed how actively I sanitize my language and how hyper-vigilant I am about the pronouns I use. Sometimes, ‘home’ as a space generates a constrained self — a self-surveilling unit that has to perform certain expectations even as they subvert others. For instance, I consciously curtail my words even as I talk to my friends about desire, trauma, and politics. Many of us talk with headphones on, in hushed tones or in secluded corners. We’ve become innovative in our everyday resistance.

Consequently, many young people from conservative family systems find alternate avenues to explore and express themselves – recreational spaces, educational spaces, online spaces, protest spaces, and so on. We cultivate different parts of our identity in these spaces, often living starkly different lives than the ones we negotiate at home. In the lockdown, we had only sporadic access to many of these physical and interpersonal spaces that previously gave us different outlets to nurture ourselves outside our homes.

There is a lack of spaces that affirm young people’s autonomy and curiosity. For many adolescents and young adults — who are curious or concerned about their bodily changes, their sexual desires, their mental health, and body image — there are very few spaces that are non-judgmental sources of evidence-based information. Having these conversations is often institutionally discouraged, pushing young people to depend on their peers, older siblings, or the internet. However, all these sources are not consistently reliable and can often perpetuate casteist, patriarchal or ableist notions. Safe spaces are crucial for personal growth and development. They provide a secure and comfortable environment for individuals to explore freely and be vulnerable. Additionally, these spaces also have the potential for the youth to question oppressive discourses that stifle expression and inquisitiveness. Thus, depriving young people of these safe spaces can have significant consequences for their relationships, health, decision-making, and agency.

During the lockdown, The YP Foundation’s Know Your Body Know Your Rights (KYBKYR) Programme, envisioned the possibility of creating virtual safe spaces for adolescents (14-18 years) from underserved migrant camps in Sikanderpur and Sheikh Sarai in Delhi-NCR. The programme views young people as individuals who fundamentally deserve to be heard and invested in, in a culture that largely sees them as subjects under care — first passive recipients and then active enforcers of caste and gender hierarchies. With this spirit, KYBKYR gives young people information about body anatomy, puberty and the physical, emotional and social changes that come with it. Further, it also discusses topics such as attraction, consent, relationships, diversity, identities, power, violence, safe sexual practices, STI and RTIs, contraception, and abortion.

Reimagining Virtual Safe Spaces

The contexts of the adolescents from Sikanderpur and Sheikh Sarai posed many barriers in accessing safe virtual spaces. First, many participants from the two migrant camps had to struggle to get access to smartphones and a stable internet connection. Quite a few young people from marginalized caste and class locations could ultimately not afford the necessary devices and couldn’t attend the sessions. Those who could, now had to attend CSE sessions on their phone screens — in their sometimes patriarchal homes — often surrounded by family members in a small space.

The safety and comfort of the physical space was an important facilitating factor in the on-ground Comprehensive Sexuality Education sessions. It established rapport, trust, and dialogue and set the stage for open conversations — in a room where adolescents could express themselves freely without fearing punitive shaming practices. The act of assembling in a physical space allowed participants to leave their homes and enter a sexuality-affirming, participatory safe space. Thus, the transition to an online space had to retain these qualities to some extent. The team relentlessly brainstormed novel ways of infusing this spirit in the virtual sessions and incorporated the following measures.

Sessions were planned and contextualised based on a needs assessment with students. It was suggested that students find a space in their environment where they could speak and listen freely and where ideally no adult would be watching over their screens. They were encouraged to use earphones and using audio and video features was left to the discretion of the students. The participants who could not talk through the audio function were encouraged to use the chat box and ask questions there. On observing that students were displaying hesitation and discomfort around saying words like sex or condom or abortion, the facilitators labelled options as A,B,C and asked participants to say that instead of saying the words.

Possibilities

“समाज के बारे में, अपने शरीर के अधिकारों के बारे में बताया, वह बहुत अच्छा लगा।“

“मेरे शरीर में क्या होता है, यह सब मुझे पता नहीं था। उस बारे में मुझे समझ कर बहुत मज़ा आया।“

I had a chance to ask the participants what motivated them to join the virtual sessions week after week. Everyone said that these sessions held an important place in their lives and helped them learn a lot about their bodies and their rights. Many emphasized that learning about different bodies and diverse experiences gave them many new perspectives.

“समाज से जो हमे सोच मिली है, वो हमे change करने का मौका मिला है।“

Some even mentioned that they reflected on the language they used to address oppressed groups like the trans community and vowed to be more sensitive. The conversations around the role of society and its policing of all that it considers unacceptable were also extremely moving and relevant for some students. It gave them a critical bent of mind and allowed them to see how society boxes and suppresses people. One participant said that these discussions inspired him to be less judgmental and also encouraged him to talk to other people about problematic societal perceptions.

“इस से पहले हमे यह पता भी नहीं था के ऐसे sessions भी होते हैं जहाँ ऐसी बातें भी हो सकती हैं। तो हम खुद ही में उलझे रहते थे की क्या सही है और क्या गलत है। आपने हमारे doubts clear करे, सब बताया, छोटी से छोटी बात, वो बहुत अच्छी लगी हमे। नये लोगो से मिल के भी बहुत अच्छा लगा। नये दोस्त बनाने का मौका भी मिला। इतने तरह के लोग हैं और इतनी तरह की सोच होती है सबकी। आप सब लोगों को मैं बहुत miss करुँगी।“

These sessions go beyond just serving an educational purpose. The digital space, during those two hours, becomes a socio-emotional safe space of personal and political discovery through an interactive and supportive community experience.

When asked about difficulties, the students talked about not having a phone and struggles of having to persuade parents to buy or lend them a phone. Some students couldn’t attend sessions consistently because of other priorities they had. Many had to travel back to their villages due to which they were occupied with different demands. Some other students also didn’t like digital modes. Despite this, the students found innovative ways to join classes. For instance, some adolescents joined through phone calls instead of Zoom calls. Some participants who lived close by met and attended the sessions together using one device. In Sheikh Sarai, the participants also proactively did reflective homework. All this speaks to the fact that they find some value in coming to the sessions and were motivated to find their way to them every week.

Without a massive resource investment, the sustainability and inclusivity of this medium are big concerns. Nonetheless, for two months in the lockdown, these online sessions were a virtual safe space. I found that as I monitored the sessions and spoke to the adolescents and the facilitators about their journeys, I too negotiated and resisted the norms of my house in new ways — speaking a little loudly about reproductive rights, and queer experiences; making a little more room for my politics and voice at home.

Creating safe spaces, community support and people’s movements are becoming increasingly important as we’re witnessing an assault on dissent and the needs of the most marginalized in our society. But when basic formal education is in crisis, what are the odds of institutionalizing feminist safe spaces for young people? Do we only care about youth from marginalized communities with respect to meeting desired enrolment rates? Or do we wish to qualitatively and meaningfully transform their learning experiences for the better? The future seems grim and arduous. For those with power, enabling young people to become informed, critical and empathetic citizens seems to be too much of a threat to the viciously exclusionary status quo.

Note: A version of this article was first published on Feminism in India in November 2020