Pandemic in an Enclave

Fatima Hamid, 26 | ![]() West Bengal, India

West Bengal, India

The Covid-19 crisis exposed many underlying challenges in our daily lives in an unprecedented way. One of the most unfortunate scenarios that came to the fore was a blame game which reinforced racial discrimination and created space for brazen Asian bashing at a global level. Such patterns of ‘otherisation’, which manifested in apportioning blame, percolated even to the micro-level. The case of Butcher Basti, a Muslim inhabited enclave in the Darjeeling hills, illustrates this point. A historically Muslim dominated enclave, Butcher Basti was subjected to criticism and rumours that the virus was spreading from here. It is interesting to map how a pandemic has allowed for deep-seated stereotypes about people and the spaces they inhabit to reveal themselves. The Basti has a long history of indigenization, where migrant labourers who were brought in during colonial times intermarried with native women. The pandemic allows for an evaluation of not just the prevalent living conditions but also of the reasons of impoverishment and lack of development in the Basti, the onus of which falls not only on the residents but also on the local authorities. Therefore, it is critical to look at the experiences of people living here and see how they have borne the brunt of a two-pronged attack: that of the virus and that of the prejudice that they have been subjected to.

The influx of the Muslim population of Butcher Basti in the hills can be traced to the migratory labour history of colonial Darjeeling. The overall Muslim landscape in Darjeeling is far from homogenous. There are four main groups that can be identified according to their ethnicities. The Kashmiri Muslims are an affluent group that have been trading in Pashmina and curios. The Bihari Muslims have their businesses in the confectionary and hotel industries. The Tibetan Muslims, who arrived from Lhasa in 1960 after the Tibetan Uprising, also deal in similar businesses. The Muslims of Butcher Basti are recognized as Nepali Muslims. Their seemingly liberal aspects of livelihood, and their morphological features make it difficult to distinguish them from the general population. But other Muslim communities do not think they are ‘real’ or ‘good’ Muslims because they adhere to the Barelvi school of thought. This means that they follow practices like wearing charmed amulets, pir-worship, nailing the thresholds of houses to ward off jinns and so on. For communities who follow other schools of thought within the Islamic tradition, such Barelvi expressions of identity are regarded as Un-Islamic.

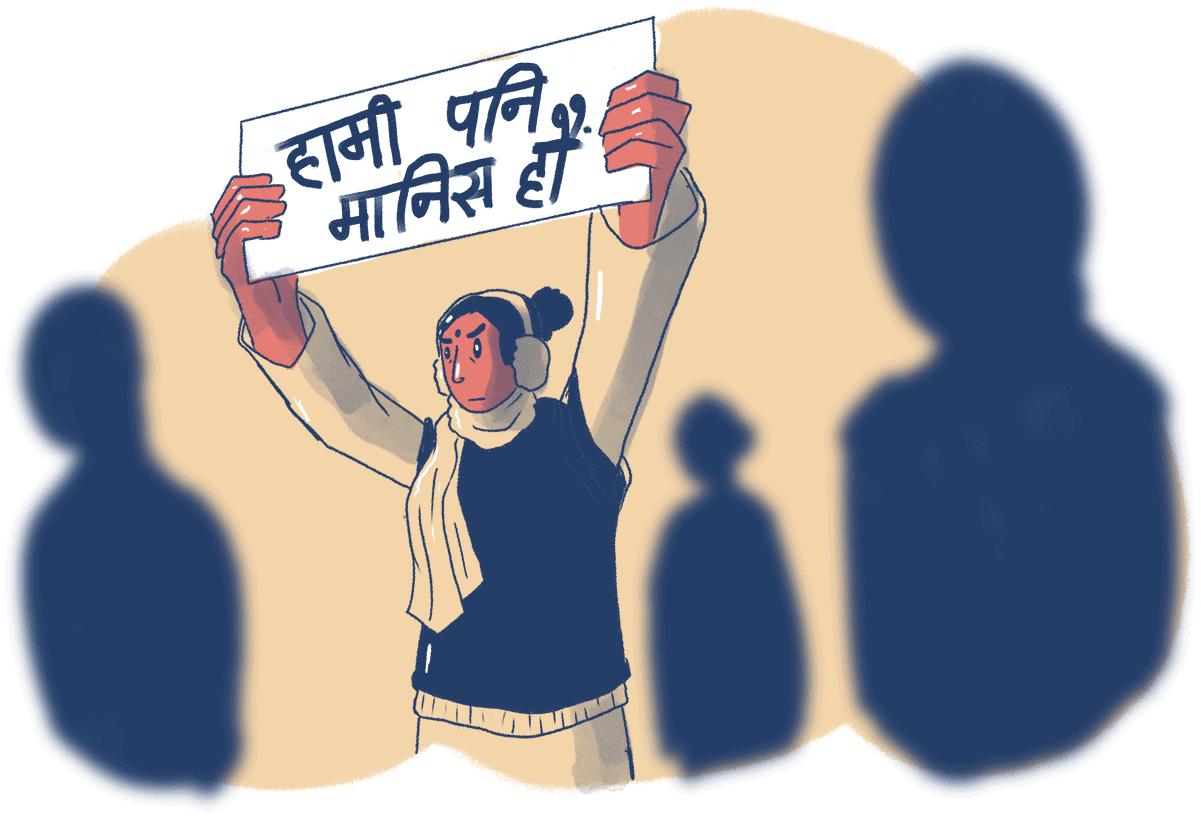

Another distinctive practice of this group is the prevalence of occupation-based caste practices that have jaati characteristics. For instance, the meat-cutters and suppliers are known to be from the Quresh jaat, the weavers are Dhunia jaat, and so on. This inter-cultural aspect of their identity subjects them to a lot of criticism among other Muslim communities, and even the general Nepali population. Eran Phuppu, a sixty-five-year-old woman remarked, “Na Nepali log accept karta hai, inharu kattu ho bhancha, aur musalman log bolta hai in log Nepali Musalman hai”. [1] (‘Nepalese people accept us, they call us kattus [2] nor do other Muslims accept us, saying that we are Nepalis’). This phenomenon of ‘otherisation’ was felt during the Covid-19 pandemic in this enclave.

Feroza Banu is a forty-seven-year-old resident, mother of two daughters working as a teacher in Darjeeling. During the pandemic imposed lockdown, she had a first-hand experience of Islamophobic sentiments that were flung at Butcher Basti. She had heard rumours that the virus was breeding here. This is not a plain statement, and the underlying anxiety of other communities reflects how normalised it has become to hold certain groups of people accountable for the pandemic simply because they inhabit a certain type of space. Feroza Banu described to me how uncomfortable she felt at such accusations. She took charge of bringing the residents together, pooling funding and providing relief to the families that were struggling during the lockdown.

Similarly, a group of six to seven young boys who call themselves ‘The Himalayan Brothers’, volunteered to provide relief. The Himalayan Brothers raised funding and delivered a wide range of services not just within their community in Butcher Basti but also in the neighbouring villages. One of the volunteers, Mohammed Azmat, explained in detail how they had provided rations which included items like soya chunks, milk, butter and many more. They also bought clothes in bulk for children aged six to twelve so that they could have new clothes to wear on Eid. During the time of Eid, they used the zakat funding raised within the community to provide for a decent stipend of 1500 rupees to many Muslim households that had been hit hard by the pandemic. The funding that was not part of the zakat was used to help people, including the Nepali communities, surrounding the Basti and other remote places like Lebong which is far removed from Butcher Basti.

Their efforts show how despite the socio-economic conditions that prevail in the Basti, people have actively participated to combat challenges. They started relief work even before the local authorities and the Anjuman-E-Islamia geared up to fulfil their duties of helping people. The Anjuman- E- Islamia is an organisation that is supposed to look after the welfare of Butcher Basti. They fell short, and organised only one campaign where they distributed only a few items like onions, tomatoes and potatoes. Unlike it, these groups of people, who are often referred to as khachchars, (hybrids) kattuas, butcheriyas, defied the stereotypes of being complacent, hand-stretching minorities. Instead they proved to be active change makers for not only their community but also for those who have treated them with contempt.

________

[1] She is alternating between Nepali and Butcheriya.

[2] As derogatory term used for Muslims