A campus fairytail

Oroosa Anwar, 22 | ![]() Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, India

Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, India

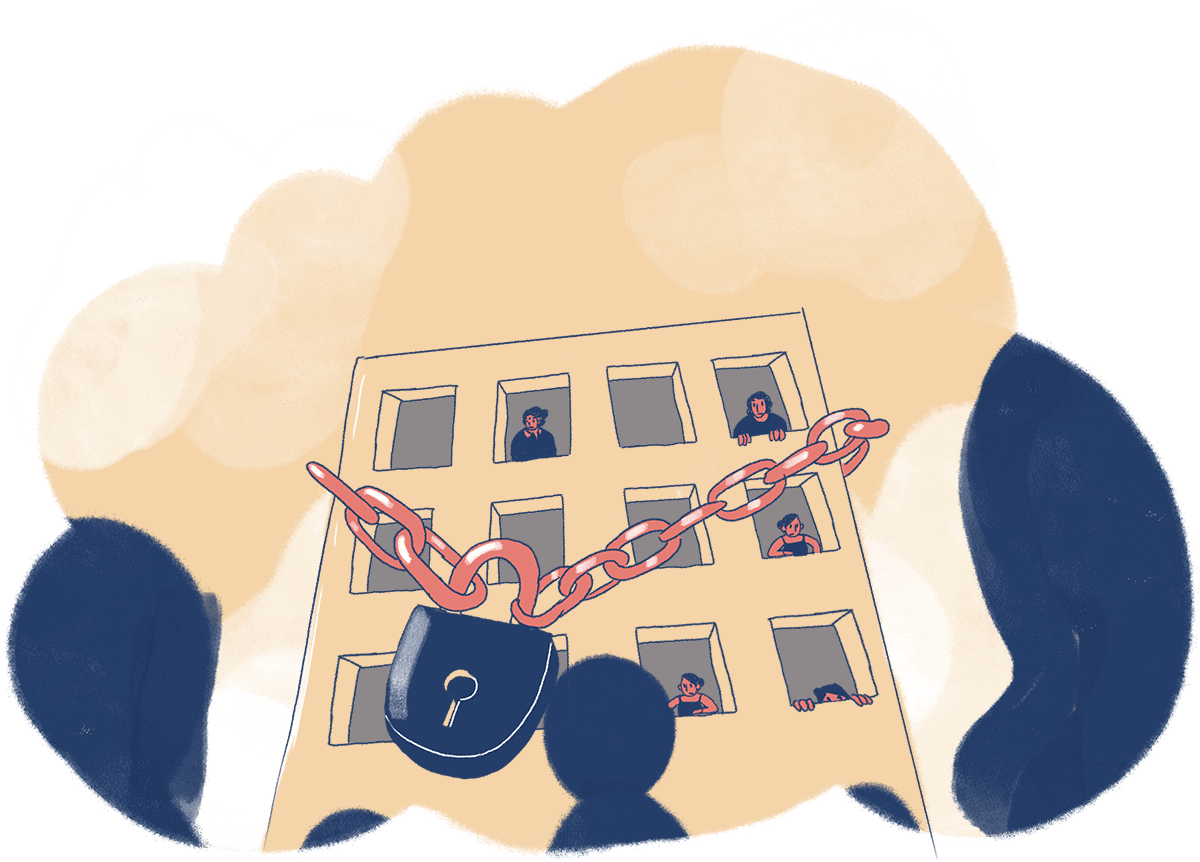

In a world where women fight for equal representation in academic, political, socio-economic, and corporate spheres, imagine a situation where women have to grovel in front of their hostel administration to be allowed to go to the nearby market. The point is not to stereotype the affinity women have towards shopping, but to highlight the exclusion of female students from the public spaces in and around the main campus, which in turn impacts their academic, non-academic, and political growth. On my university campus, the women are dubbed as Shehzaadiyan (Princesses), and rightly so, given that the administration thinks we need to be locked up to be protected. Regardless of our age, we are unable to exercise even the tiniest amount of agency when it comes to our mobility.

The university I attend has cultural reasons for restricting the mobility of its female students. Having been established in the colonial period of India, it has carried the tradition of overly sheltering women into the twenty-first century. Thought of as the weaker sex, there are strict limitations on how long women can stay out for and special outings are granted only when sufficient proof is provided of the student’s necessity to go out. Institutionalising the fear that Indian parents have regarding the safety of their daughters, [1] the administration rounds up its resident female students into their respective hostels before sunset; even Cinderella had till midnight. Worse, they make no distinction between minor students and adult research scholars, essentially treating all women as children. Painfully, this norm is advocated by parents despite the progression of time into the twenty-first century.

If restrictions on our mobility weren’t frustrating enough, what is particularly painful is the autonomy given to the university’s male students in every aspect. When the lockdown came into effect in March 2020, the university’s female hostels were the first to impose complete shutdown, but the male hostels did not. Where women worried about going to the ATM as they did not have enough cash to manage expenses in such difficult times, the university permitted its men to roam about freely. Almost as if the Coronavirus too rooted for gender discrimination. Every time we approached the hostel administration, requesting them to let us leave the hostel for personal reasons, they would talk about the great debt we owed them for allowing us refuge in the university during these troubling times. Their attention was focussed on the relevance of our reasons to go out, and each reason was disregarded. The provost of our hostel, who happens to be a gynaecologist, told me that “Haan abhi sab depression mein hain” (Yes, everybody is depressed lately) when I reminded her of the impact of a nine-month long isolation on mental health. The warden suggested we take a walk in the hostel lawns if we ever felt overwhelmed by the walls, as if we were animals. In a span of nine months, I left the hostel premises about six times after proving the urgency of my need to go out. Of course, I had to return within an hour.

The initial phase of the lockdown required people to stay indoors, which was the need of the hour, but my complaint lies with the university’s overindulgence in the ‘protection’ of a specific gender while threatening their basic human rights. In contrast the male students did not ever have to face any kind of inconvenience on count of their mobility. We were caged in the hostel even after the Indian Government relaxed its lockdown regulations. The entire university teaching and non-teaching staff, the male students, and female MBBS students were free to move about in public spaces while following the standard safety regulations (or not). A handful of women who were not as privileged as males or MBBS students had to abide by a continued lockdown.

By curbing my ‘frivolous’ outings the university actually prevented me from wasting time. Thanks to this abundance of time I had on my hands I was able to channelise my energy into productive activities. I volunteered at Teach for India, teaching 10th standard girls core English, and helping them develop their communication and language skills. In a span of five months, I noticed that the girls who were hesitant in speaking up earlier engaged in classroom discussions more openly; their literary skills improved; and most importantly, their desire to learn and grow through education increased. Some students also revealed that due to the shortage of mobile devices at home, their brothers were prioritised over them for getting an online education. I also organised a session on sexual harassment awareness for my female students and made sure that they were comfortable to speak about their experiences. The girls, much to my surprise, exhibited a powerful attitude by offering encouragement and comfort to each other. My involvement with this organisation has urged me to look beyond my privileges as a student and understand that cultural issues are also affected by financial and economic factors. Interacting with young and bright girls from different economic backgrounds was an enlightening and empowering experience that I will always cherish and view as a source of inspiration for future endeavours.

As a poetry performer, I wrote poems on gender and equality to be performed at conventions of the Indian Association for Women’s Studies. The intellectual energies of the audience charged my spirit with optimism for a better future where harmony exists between differences. As a freelance content writer, I brushed up on my writing skills by working tirelessly for entrepreneurs and businesses. And yes, I managed to write a good dissertation for my master’s! I guess, at this point, I can be a shehzaadi who is not curbed by the definitions others make for her. Instead, I am somebody who builds herself through experience, hard work, and a little bit of rebellion.

________

[1] Not trying to belittle this concern; their worries are legitimate, given the worsened state of security for women in India