Resisting Narratives of Hate

Eisha Choudhary, 28 | ![]() Delhi, India

Delhi, India

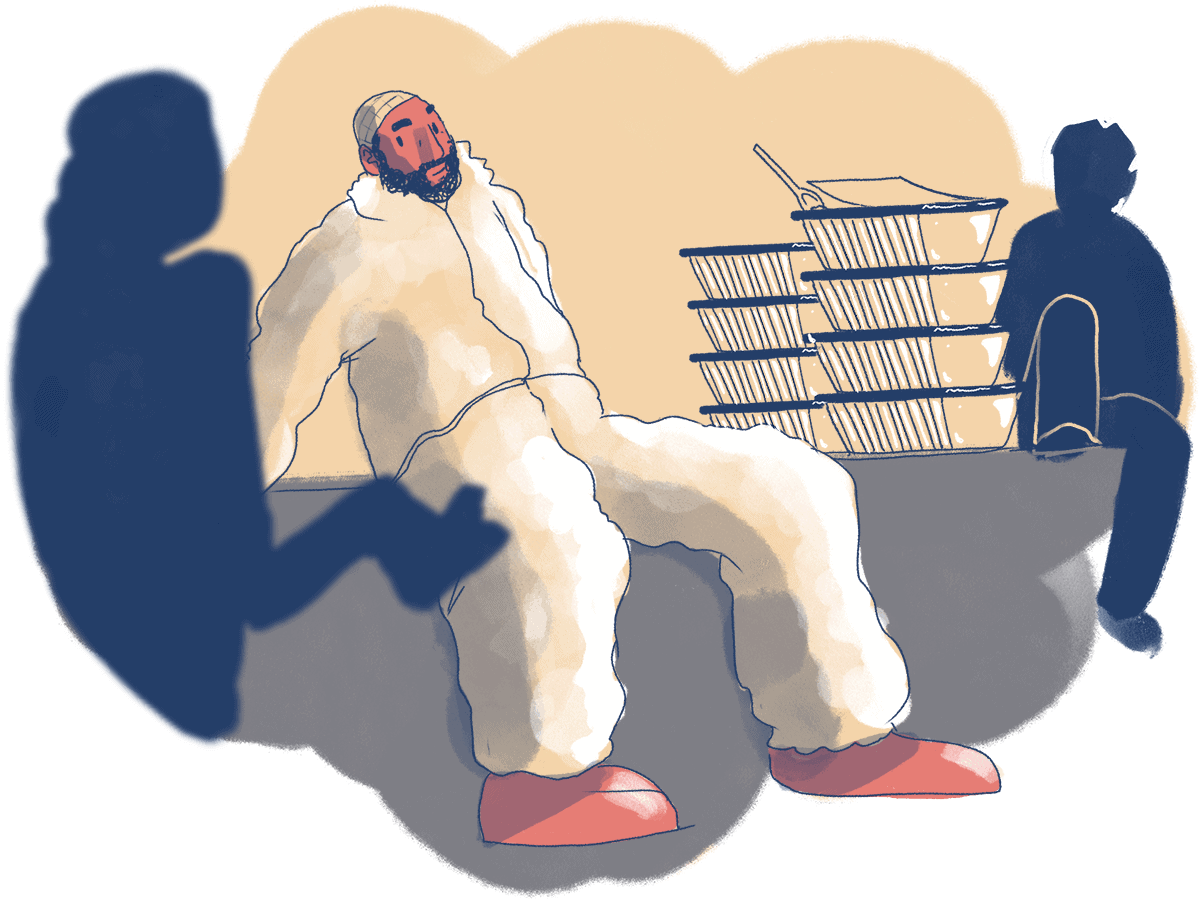

As the muezzin would give the call for asr namaz (prayer), Anas would rush, taking cooked food to a stall on the main road in Abul Fazal Enclave in Jamia Nagar, a Muslim dominated colony located opposite to the banks of the Yamuna. He would quickly set up a table and put one banana, two dates, and two spoons of boiled chickpeas in each of the neatly spread silver plates. Before sunset, people would line up, standing six feet apart taking their plates, some to break their Ramadan fasts, and others to have the only meal they could find.

It was the month of Ramadan. The bustling streets of Jamia Nagar were dead silent because a strict lockdown had been imposed in the country. In any other year, during Ramadan, men, women, young and old, labourers, professionals, and entrepreneurs would have gathered around shops which sold fritters, meatballs, jalebis, and dates as the sun would prepare to set. This Ramadan was different. There were no celebrations, no crowded shops, no flocks of people rushing to find a place in the masjid, or people bargaining with the food sellers. The silence on the streets was haunting, and people would talk in their homes about how it didn’t feel like Ramadan.

Anas is a young social work graduate, running an initiative to support the education of slum and street children in slums of Shram Vihar in Delhi. Disturbed by the plight of people in the slum community during the lockdown, he decided to set up food stalls at different places to provide two cooked meals per day to anyone who was hungry. A common practice among most Muslim households during Ramadan is to send across iftari (food-filled plates) to their neighbours, the mosque, and the underpriviledged. Anas called on his neighbours to keep alive the spirit of compassion by giving food to those in need during the COVID-19 lockdown. In response to his call, many people came with food from their houses to serve migrants and daily wage labourers.

What was unique about Anas’ initiative was that it was community-driven and did not rely on any fundraising campaigns. While he served rice in the initial days, on the request of the labourers to be served rotis, he started another campaign, ‘2 rotis extra’. He believed that if each house could give two rotis, they could help people who would have otherwise slept hungry. People from nearby areas immediately joined him in his campaign. Every evening by 8 o’clock hundreds of rotis would be collected and distributed along with curry or mixed vegetables cooked by a few other volunteers.

The same routine of praying, collecting rotis and serving food to the migrants continued even after Ramadan. As people would leave after eating the food, they would give good tidings to Anas and the volunteers. Many other young Muslims in the city, as well as in the rest of India, were actively engaged in helping disadvantaged fellow human beings during the COVID-19 lockdown. Visuals of Muslim men helping migrants walking barefoot with food, water and slippers were seen across social media.

Despite this, as I have argued earlier, voices of Muslims and their acts of being responsible citizens are overshadowed by the loud narratives which frame Muslims as ‘others’. During the pandemic, Muslims were targeted and blamed for deliberately spreading COVID-19 in the country. Media channels and social media platforms were flooded with hate speech against Muslims which translated into real life threats and abuse.

Not long before the COVID–19 lockdown was announced, Delhi had witnessed an anti-Muslim pogrom due to which thousands of Muslims were displaced. The loss of life, livelihoods and property had left Muslims in the affected areas of North East Delhi especially vulnerable during the lockdown. With the pandemic, their sufferings further deepened. The shelter homes, where the victims had been placed, asked them to vacate the place following the COVID-19 guidelines issued by the government.

When Yusra, a Muslim woman living in Jamia Nagar, visited the pogrom affected areas of North East Delhi, she was shocked, sad and disheartened with what she saw. She described that when women met her, they begged her for food and money, showed her empty ration containers; children kept crying because they had not eaten for days. Concerned with the desperate state of affairs, she immediately contacted other organizations engaging in relief work to collaborate with them. Yusra then led a team of volunteers to pack ‘COVID-19 Safety Nets’ which carried ration for one month, sanitary essentials, masks and gloves. Dressed in PPE, Yusra carried these kits to Khajuri Khas, and neighbouring areas in North East Delhi to help people overcome the crisis of food, and empathy.

Yusra is a passionate social worker who also runs a social initiative for street children, engaging them through sports to develop life skills. Through her contacts with partner organisations, Yusra launched various campaigns to not only help people with ration kits but also to create awareness about the precautions they should take to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in slum communities. In her experience, people had various misconceptions about COVID-19; initially people thought it was a rumor or fake news. There was also a lack of resources to practice regular handwashing and maintain social distancing. Yusra formed groups of adolescents in the community and told them accurate facts. The adolescents then took the responsibility of making sure that COVID protocols were followed in their community with the limited resources available.

The initiatives led by Anas and Yusra documented here did not take shape in isolation but were the result of coordinated efforts of people and communities coming together to help the underprivileged. Whatsapp groups were created where volunteers from different parts of the cities took charge of distributing relief materials in their concerned areas. It is pertinent to view the philanthropic initiatives of young Muslims in the context of the teachings of their religion. Embracing the call of Islam, to give charity and extend solidarity to the poor, young Muslims envision a world where people share each others’ grief, pain and helplessness. The active engagement of Muslim youth in relief work, and the support they provided during the lockdown must be celebrated as resistance to the narratives of hate. It is heartening to see that young Muslims have not been deterred, and continue to engage in philanthropic acts. How long will it take to acknowledge that Muslims are active and equal citizens of the country?